Niall and Style A presentation by Prof. Roy Foster, Emeritus Professor of Irish History, University of Oxford, as part of "Aerial - Symposium celebrating Niall McCullough: architect, writer, thinker" on 4th November 2022 at the Provost's House, Trinity College, Dublin.

Niall was as stylish a historian as he was an architect and I want this evening to convey - if I can - something of that inimitable style. The advice given by the great historian of Victorian Britain, G.M. Young, was to ‘read until you hear the people talking’. Niall read buildings and streetscapes and landscapes till they talked back to him, and we are all the beneficiaries of that conversation. He interpreted Dublin’s streets like James Joyce did, and his book Dublin: an urban history would, like Joyce’s Ulysses, enable an exile to reconstruct the city. It did that for me.

When I read it, I looked in a new way at the places I lived in the inner city as a student in the late 1960s and early 1970s-first of all bedsits in Great Denmark Street and Wicklow Street, then a rambling flat in the Corn Exchange Buildings, fronting the horror of Hawkins House and usefully flanked by the Scotch House and Mulligans pubs- a conjunction which provided Niall with one of his riffs on corners. His treatment also illuminated my later halting-sites- half a terrace house in Ranelagh and then a cottage-style house in Lombard Street West (an address once shared by Leopold Bloom). To walk into the city centre from either of these places took you down Camden Street and then Aungier Street, traversing a chapter of urban history brilliantly expounded by Niall.

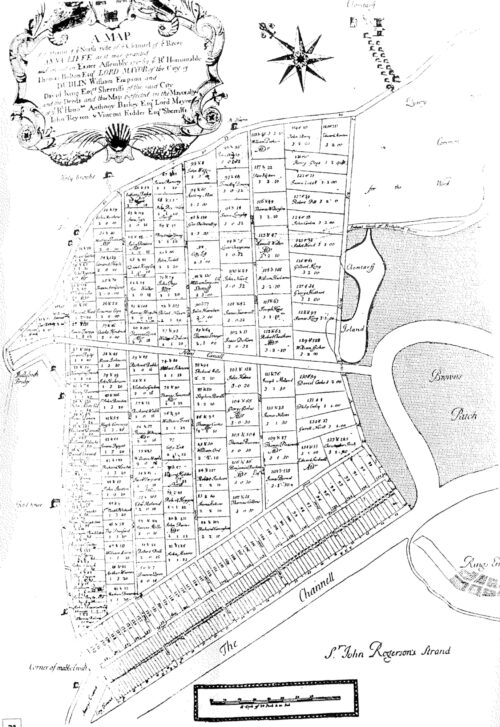

That view from a suspension-point above, which Niall manipulated so authoritatively, enabled him to see the city as an accumulation and palimpsest - a favourite word. His acute sense of historical context illuminates the religious dualism evident in the city’s architectural evolution, as well as enabling - for instance - a brilliant comparison of ChristChurch Cathedral with St Patrick’s and tracing how Georgian Dublin combined planometric discipline and - in Niall’s phrase - ‘voracious adaptability’. He shows that leases and their complications are as influential in the city’s development as aesthetic fashion. He sustained a historical vantage-point which gave him an unerring sense of place as well as placement (the Irish word for ‘Place’, ‘lios’ designated - as he pointed out - much more than simply an area: it’s a carefully bounded space). Digging below the plans of a Humphrey Jervis or a Francis Aungier, Niall’s historical treatment of Dublin gave correct precedence not only to the ancient religious geometry of the city but to its extraordinary setting between mountains and sea and its magnificent bay. Always acute to European parallels, he invoked the marine beauties of Lisbon, Cadiz and Genoa (on one occasion comparing the latter’s Strada Nuova to Henrietta Street). He read the quays and their development with an inimitable command of geography and metaphor, vividly painting what might have been as well as what transpired.

Thus he traces out the intended development of the North Quay in 1717: showing the planned infill of the bay out to Clontarf, and the grid of streets with grand titles. But, instead of nearly doubling the city’s area, the development short at the East Wall Road, and Victorian urban history pushed it in another direction; though, in Niall’s words,

‘James Gandon, taking up the curve suggested by the old coast road to form Beresford Place, located the Custom House on the knuckle joint between city and sea.’

That ‘knuckle joint’ metaphor is quintessentially Niall, as is the Joycean sweep of vision, re-creating a then-forgotten tranche of the city (which has recently, of course, undergone another kind of transformation). Niall was as sensitive as Joyce to Dublin’s ‘environs’- threatened by corruption and unchecked “development”, sanctioned by authorities which often merrily acted as estate agents rather than as monitors of the built environment. He wrote about the life of the city and the way an urban organism lives and dies. He knew the dangers of sterility and rigidity, or the development of the kind of dichotomy expressed by Paris within and outside the périphérique. This consciousness lies behind the audacious creation of a library in the sky on the roof of the Dental Hospital, or another Library at Rush, worked into an adapted church by the sea. This conversion was made by an intervention in the church nave; Niall described it as ‘an inverted U with two galleries… Its tense gravity like that of a page folded from a book, or a paper aeroplane; flattened out it appears like a pattern for a suit of clothes or a cut-out from a cereal packet; pulled taut, it has a kind of unreliable stability.’ The vivid similes bear the unmistakeable imprint of Niall’s style. His description of the Rush Library elsewhere expresses his sense of place with similar punch:

"Rush is surrounded by a gridded landscape overlaid by a suburban sprawl which owes its particular form to the field network beneath it. You can still step onto the earth to pick up a cabbage; there are sandy paths between greenhouses to the sea. Lambay Island is visible between the houses, mythical, like an island in a Tintin book, mute, unattainable."

Everyone here knows more about the language of architecture than I do, but as this quotation shows, the point of Niall’s writing is that he also spoke the language of history and social anthropology. He read buildings like Bachelard, and landscapes like Sebald. ‘Each generation’, he wrote in Palimpsest,

"steps away from its built artefacts as in a hall of mirrors - early familiarity, contempt and dismissal, then the building as representative of an age, then curiosity where information is lost and later re-invention to suit a creative process of mythification. The Romantic sensibility is always at play - the sense of loss and a search for beginnings that leads eventually to the re-use of forms as symbols- a process which influences, as it passes, the form and character of the older buildings it feeds off, as they are themselves altered to suit the pre-ordained theory of the beholder."

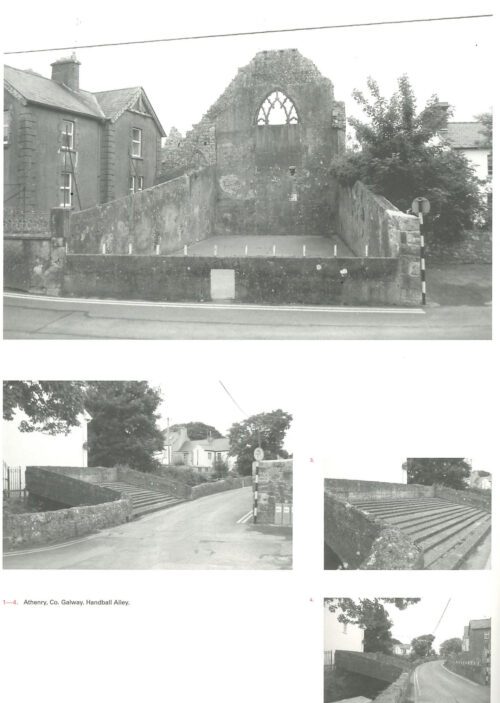

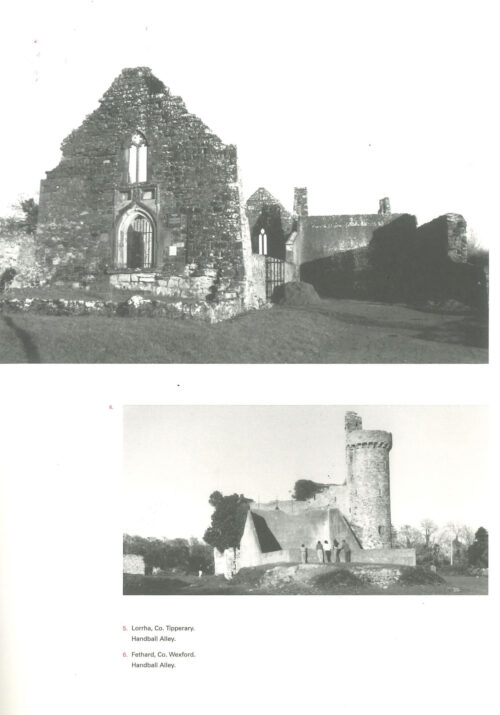

This reminds me of the way that, as another historian once put it, we tend to imagine the past and remember the future, rather than the other way round. Niall’s understanding of symmetry and repetition in historical as well as aesthetic terms underlay his appreciation of the layers of life built up through destruction as well as construction, seen in his appreciation of Chipperfield’s Berlin Neuemuseum or the Kolumba Museum in Cologne. That same comprehension dictated the consummate way that he and Valerie introduced the new while maintaining the footprint of the old in so many of their buildings. In his books he traced how buildings can themselves respond to historical change by morphing, absorbing, changing - the tower house with a farmhouse grafted on, the abbey that becomes a dwelling house - and, less predictably but delightfully, the evolution of handball alleys.

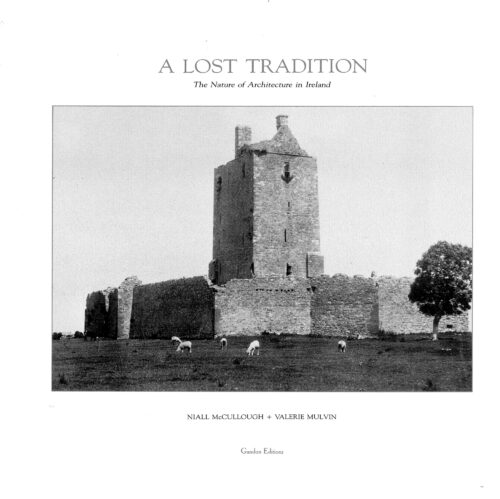

That epitomises the approach he and Valerie delineated in A Lost Tradition, published like the Dublin book in the late 1980s. It approached the history of the built environment with empathy and historical acuteness as well as architectural expertise, in the manner of Maurice Craig, Marc Girouard and Christine Casey. But it was remarkable for its range and the originality of its organisation. It used spatial analysis and an unerring eye to uncover underlying patterns of connection, as in the discussion of a collection of buildings at New Haggard, Co Meath. The mill,

"Its slightly crooked angle to the river giving it a washed-up, accidental air… forms a triangle of elements with a ruined tower-house in the next field and the cubic mass of the miller’s house on the hill; the ruined tower of St Mary’s Abbey in Trim (itself castellated) is visible on the skyline. The tall, thin end elevations of Georgian sashes crossed with castellations has something of the fantastic about it, like an experiment by Ludwig of Bavaria, or a sketch for the backdrop to some operatic scene."

This shows a painter’s eye as well as a literary gift. Above all, there is an acute recognition of the way that architectural and aesthetic tradition projects forward through juxtaposition (and, occasionally, fruitful accident). The eye for detail (and occasionally mischief) slots things together like a Sean Hillen collage. We see how domestic typography echoes forward into mills and almshouses and charter schools, and how oppressive legacies from forts and barracks are tamed, tempered, and even redeemed into new uses. As in the Dublin book, we are given close readings of places and European parallels. A survey of forgotten provincial beauties in places such as Athy and Nenagh remind us of what McCullough Mulvin have done in Sligo, Waterford and most recently Kilkenny, with their prizewinning Butler Gallery, and plans for St John’s Church.

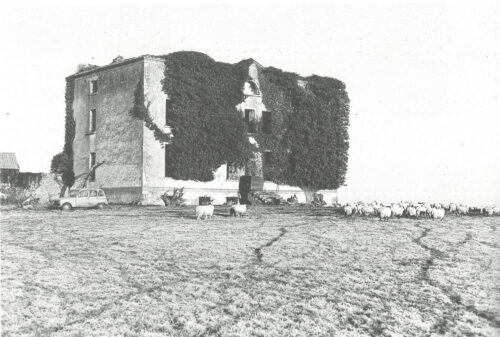

But Niall is equally conscious of destruction (that ominous ‘D’ in brackets after so many illustrations stands for ‘demolished’). Discussing Station Island in Lough Derg, he refers to Ireland’s ‘architecture of perpetual fragments’, and his books are full of pictures of ruins.

(In this beautiful photograph, I told him that I liked the inclusion of the farmer’s car, and received the mock-offended reply: ‘That is our Renault 4.’) It’s more inspiring to reflect that, from the vantage of the great Burlingtonian mansion we’re in tonight, we can see at least one McCullough Mulvin building, the stunning Long Room Hub. As we’ll see tomorrow, what their practice has done for Trinity is emblematic of so much that Niall drew attention to in his writings. In the Dublin book he writes evocatively of the way that the first courtyard of the original college lingers like a ghost, while the expanding pattern of the institution discards its earlier sections ‘like [bits of] the egg it had hatched from’. His and Valerie’s work within the College walls recognises the need to address surroundings sensitively- In the case of the Hub building, the challenging panoply of spectacular buildings around it, all theatrically different). There is an intense consciousness of how to use light and space in a place of study. He anticipated this long before in what he wrote about Thomas Burgh’s great library block of 1712 - ‘designed as a galleried reading room on an arcade or piazza, flanked by pavilions containing staircases and librarian’s apartments; Victorian alterations enhanced its architecture by removing the gallery and throwing both levels of bookshelves into relief as apparent supports for a barrel-vaulted roof, the space appearing literally to be made of books with the light filtering between them.’

In its combination of restraint and chutzpah, the Long Room Hub building epitomises what John Millington Synge told W.B.Yeats was the foundation of style: “the shock of new material.” Niall knew this as a writer and historian as well as an architect. But he also knew how to value, respect and where necessary incorporate, the impact of what had gone before. It is Ireland’s - and perhaps particularly Dublin’s - loss that other keepers of our architectural heritage have been so slow to recognise this. In celebrating his work this evening we salute a pioneering spirit and an original writer as well as architect, bitterly missed. But - thinking again of the Hub building - we remember too his fascination with the ‘Meeting Houses’ which he and Valerie wrote about so eloquently in A Lost Tradition: places where people (often from excluded out-groups, such as Quakers) came together for intellectual and spiritual exchange, in buildings which epitomised the volume, space and light conducive to such endeavour. And that illustrates both Niall’s approach, his achievement, and his style.

—Prof. Roy Foster, Emeritus Professor of Irish History, University of Oxford