-

Rafael Moneo - To Build in One's City, Building in Madrid

Inaugural Niall McCullough Lecture Series, 25th April 2024The work of Rafael Moneo’s studio has had a profound influence on the work of McCullough Mulvin, and indeed on the work of a whole generation of Irish architects.

-

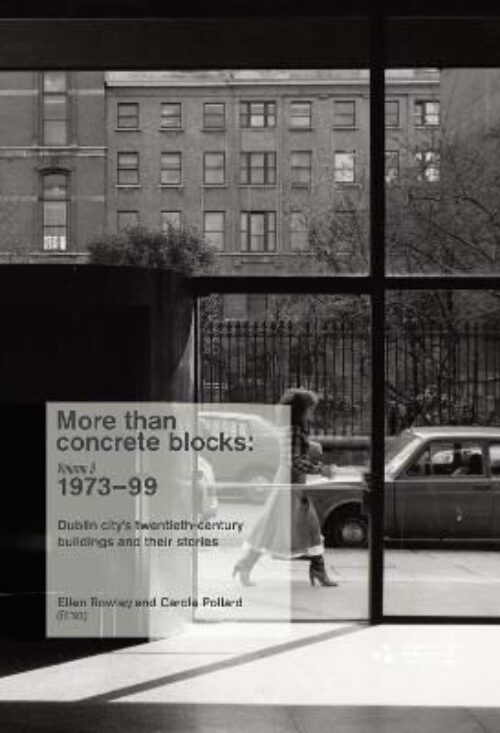

Launch of "More Than Concrete Blocks Vol. 3: 1973-1999" edited by Ellen Rowley and Carole Pollard

Valerie Mulvin1973. The year the marriage ban ended. I did my leaving cert. The Pidgeon House towers were built. The arc of this quite fascinating book, the final one in the three volume series beginning in 1900, covers years intensely familiar to me – and I suspect to many people in this room.

-

Introduction to Aerial Symposium

Dr. Linda Doyle, Provost, Trinity College DublinIn Trinity, our campus is the way it is partly because of McCullough Mulvin...one of the highlights that has happened... is the opening of Printing House Square

-

Aerial - Symposium celebrating Niall McCullough: architect, writer, thinker

A celebration of Niall’s life, work and ideas was held on 4th November 2022 at the Provost’s House, Trinity College Dublin.

-

Niall and Style

Prof. Roy Foster, Emeritus Professor of Irish History, University of OxfordNiall was as stylish a historian as he was an architect and I want this evening to convey - if I can - something of that inimitable style.

-

Excerpt from "Dublin: Creation, Occupation, Destruction"

James Conway, Former Director of English Touring Opera reads from Niall's last book -

Niall McCullough i gcuimhne

Ricardo Meri de la Maza, Universidad Politécnia de Valencia and Editor of TC Cuadernos“A man is original when he speaks the truth that has always been known to all good men.” Patrick Kavanagh

-

Looking East - Campus as Laboratory

Rajeev Vederah, Chancellor, Thapar Institute of Engineering & Technology, Punjab, IndiaOver a series of discussions, Niall demonstrated to us how the built environment played such an important role in the development of the campus life, and how it could leave a lasting impression on students and staff.

-

A Blast of Magnificence – Niall and Architecture

Shelley McNamara, Grafton ArchitectsThe eye peering over the easel in this photo is that of Oscar Kokoschka... This photograph in some way seems appropriate in talking about Niall McCullough.

-

Architecture and Time: An Architect's Vision of History

Prof. Christine Casey, Trinity College DublinI can think of no better words to evoke Niall’s vision of history than those of a famed mentor, Aldo Rossi, with whom he shared a deep sensitivity

-

Introduction to "Aerial" film made for Open House Dublin

Nathalie Weadick, former Director of the Irish Architecture FoundationI first met Niall about twenty years ago when I was director of the Butler Gallery in Kilkenny.

-

A Good Kicking

Eddie Conroy, Former County Architect, South Dublin County CouncilMy dictionary tells me that a symposium has two requirements; the first one is that the speakers are knowledgeable about the topic whereof they speak, and the second one is that the topic is of crucial importance. So, I think there’s no doubt about the speakers, and we are all here to celebrate the life of this marvellous man, Niall McCullough.

-

Creative Partnership

Valerie Mulvin, McCullough Mulvin ArchitectsWe started working together very early on in our careers and had an incredibly creative partnership over a very long time. Work was always inspired by looking deeply at architecture, ancient and modern, and investigating it by drawing

-

Housing Unlocked: Join the dots – 100 small ideas for sustainable change

Housing UnlockedVacancy and dereliction blight the centres of our towns and villages. Why? Because nobody is thinking about them with imagination as the brilliant spaces they could be...

-

Remembering Niall McCullough (1958-2021)

-

Villa Shodhan - Introduction to Manisha Basu

Ruth O'HerlihyEight weeks ago I was plunged head first into the most exciting place I have ever been to. It was also the hottest. In Ahmedabad, where I was warmly welcomed by Arthur Duff (of CEPT University), we had an exhibition opening on 3rd April. The exhibition was in CEPT, in the new library which now focuses the campus designed by Doshi. When you are there the voice of the master resounds, the buildings feel like they have and will be there forever, fulfilling their role as inspirational space for teaching.

-

Introduction to "McClean Design: Creating the Contemporary House"

Valerie MulvinI have a strong memory of Paul McClean and two models he was working on almost thirty years ago in Dublin—artists’ studios in Temple Bar and an extension to the Abbey Theatre.

-

Words on the opening of Displaced Longitude at CEPT University, Ahmedabad - 3rd Apr 2019

Ruth O'HerlihyThe greatness of India lies in its people, its landscapes, its cities and in the gigantic armatures built to house ordinary lives – elegant and logical architecture ameliorating a hot climate, allowing commerce and conversation to flourish in shady halls.

-

One House at a Time - Making contemporary Architecture in Georgian Dublin

Niall McCulloughThe practice is working in No. 11 Parnell Square for a dynamic group of agencies (the Irish Heritage Trust, the Landmark Trust and Poetry Ireland) who have come together for the purpose of restoring and using the house in a new way - transforming it from a set of static offices into a public space for discussion, meeting, music, poetry and the spoken word.

-

Practice history & context

McCullough Mulvin’s architectural practice has produced striking contemporary works- in Dublin, in Ireland and, further afield, in the Indian Punjab. Putting an order on what the practice does is not straightforward; there is no one way of making form, no signature shapes, more an attitude and a methodology- if the work is about anything, it’s about place.

-

Ribbon Development - Ballybough Student Housing

Ruth O'HerlihySometimes a site and a brief give unexpected results. Ballybough is a dense and fascinating part of Dublin riven by railways and canals, streets full of unusual residential typologies, Croke Park rising behind every vista. The brief was to provide accommodation for 284 students along with cafe and ancillary services, and a landscaped courtyard.

-

Cork - A Place

Valerie Mulvin, The Cork PapersIn Cork, the city extends well beyond the centre; it is about the river downstream and its small towns and villages, the river widening and narrowing until it explodes out into the majestic harbour with its big-boned modern facilities guarded by remarkable 18th and 19th century fortifications and stone beacons- a mix of entirely technological and completely ancient things, both protection and memorial.

-

McCullough Mulvin Orange

Niall McCulloughMark Orange’s enquiry takes five buildings in Dublin and focuses on one of the architects who designed them. The architect - interested in the city, in architecture place and memory - is called on to revisit the structures after a period, to look on them or explain them. The result is recorded - visually and aurally.

-

Blackrock Quartet

Hugh CampbellThe town hall is first to arrive on the scene. The authorship of this neat, Italianate hall, completed in 1865 is in some dispute, but its intent and its impact are not. Into a street of residential and religious buildings it introduces a note of civic importance, cementing the status of the newly established Blackrock township.

-

Losing the Plot: McCullough Mulvin’s extension of the Dublin Dental Hospital

Kevin DonovanThe demarcation of ownership of a piece of ground by enclosure, or ‘plot’, projects an upward effect; it underpins the architecture that is made above. The consecutive speculative development of plots has largely determined the form and character our city has taken. Adherence to a system of these thin strips of land with limited street frontage has, for us, meant terraced streets and party- walls, with generous openings lighting tall, stacked rooms, both front and rear.

-

A Found Tradition

Roy FosterIn 1987 Niall McCullough and Valerie Mulvin published A Lost Tradition: the nature of architecture in Ireland. This trailblazing and beautiful book traced the evolution of Irish architectural forms for the ‘mound and circle’ of prehistoric sites, through ecclesiastical monuments, fortified plantation enclosures, vernacular farmhouses and bravura Georgian mansions, to the institutional architecture of modernity.

-

Introduction to an Introduction: On the Work of McCullough Mulvin

Mark DorrianThere is a small engraving that is reproduced in a number of publications by Niall McCullough and Valerie Mulvin. It first appears at the beginning of their 1987 book A Lost Tradition: the Nature of Architecture in Ireland, where is occupies the page before the main body of the text, a location that suggests it acts as a kind of allegorical frontispiece to what follows. In writing the present introduction to the work of these architects, I want to dwell on this image – which is itself positioned as a kind of introduction, not just to A Lost Tradition, the first of their books, but to their body of work that will thereafter unfold – for it seems to me to cast light in important ways on the work of the architects.